The plight of tropical migratory species

So much remains unknown about the tropics, including the extent to which species living in these environments migrate seasonally. Dr Lisa Davenport has worked for many years in the tropics, especially the Peruvian Amazon. Here she tells us about her intriguing work on a particular migrator, and its broader implications for nature conservation:

A foraging Black Skimmer

An unknown number of tropical species, such as certain birds, bats, and moths, migrate up and down elevational gradients over the year, tracking seasonal changes in the abundance of fruits, nectar, or insect prey.

Others, notably birds such as warblers and some raptors, undertake much longer-distance migrations, wintering in the tropics while breeding in far-away temperate regions.

Manu National Park in Peru, where I have long worked, also has its share of migrators, along with being one of the most biologically stunning places on Earth. Certain fish, birds, and mammals at Manu appear to move large distances during the course of the year.

But as we begin to learn more about these migratory species, we increasingly suspect they could be vulnerable to escalating human pressures in this region.

Growing pressures

For instance, just downstream of Manu, on the Madre de Dios River, huge areas of river and riparian forest are being devastated by illegal gold mining. Among these impacts is contamination of the rivers by toxic mercury, which is used by miners to separate gold from river sediments.

An illegal gold miner scours the forest soil (photo by William Laurance)

Since 2010, biologists at Cocha Cashu Biological Station at Manu have used cutting-edge satellite telemetry to track some of the park’s rare and endangered birds -- many of which are very poorly known. One key reason to do this is to learn where these species go when they move outside the park, where they may be highly vulnerable.

In a new study, I and my colleagues report our research on Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger), an elegant bird that skims over water surfaces while flying, in order to catch unwary fish. To do this it uses its uniquely elongated lower beak, which it drags through the water and which instantly snaps shut when it contacts a fish.

We found that Skimmers tagged in Manu move extremely long distances both during and outside their breeding season.

A Black Skimmer feeds its chick

'Albatrosses of the Amazon'

I would liken our Black Skimmers to “Albatrosses of the Amazon" -- they fly surprisingly long distances, even in the breeding season, and seem to soar effortlessly.

We found that some Black Skimmers move not only to other watersheds in Peru but even to other nations, including Brazil and Bolivia, during their breeding season. Unfortunately, some of these areas are being severely degraded by illegal gold mining.

Remarkably, some of the birds tagged inside Manu even crossed the Peruvian Andes -- flying above 5,000 meters in altitude to cross the towering Andes mountains -- in order to spend their non-breeding season along the Pacific coasts of Peru and Chile.

But the Skimmers face hazards on the Pacific coast as well. Many of the natural wetlands they need for feeding are being severely depleted by the extraction of freshwater for agriculture.

Some Skimmers may go even farther afield. One bird radio-tagged in Manu moved not to the Pacific but southeast to Bolivia and then even further to Paraguay. Its transmitter stopped at that point but it may have been heading to Argentina’s Atlantic coast, where large numbers of Skimmers are known to summer.

New threats on the horizon

With rising development pressures, threats to large-distance migrators like Black Skimmers will only increase. Both Peru and Brazil plan to dramatically increasing the damming of wild rivers in the Amazon and Andean headwaters. Agriculture and mining activities are also expanding apace.

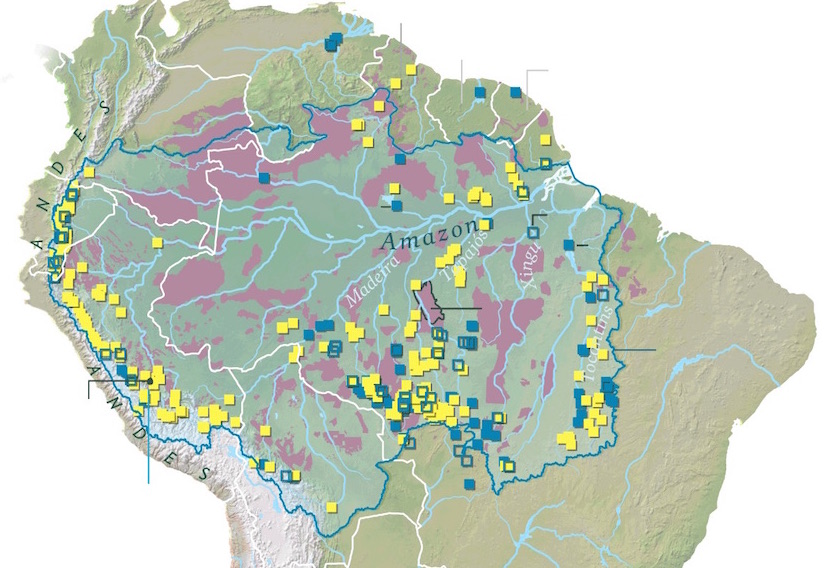

Scores of new dams are being planned (yellow) in the Amazon-Andes region (blue symbols indicate existing dams).

Species that need freshwater for survival and migration, and the ecological processes that sustain such species, will be intensely vulnerable.

The recent collapse of a poorly constructed mining dam on the Doce River in Brazil devastated aquatic wildlife across a vast area that stretched for more than 500 kilometers to the sea.

The lax environmental standards that allowed this catastrophe to occur should give us all pause, as we consider the avalanche of new development projects slated for the greater Amazon region.

Especially alarming is how little we know about the ecology of the Amazon and its many natural denizens -- some of which evidently traverse and require vast areas of habitat for survival.